An Unending Display of Courage

The Staff of Satirical Magazine Charlie Hebdo Accepts the Daniel Pearl Award

BY PATT MORRISON

To this very day, and throughout the world—and often in the farther reaches of the world, whether a firefight in Syria or a park in Guatemala—journalists are getting murdered just for being journalists and practicing their craft.

But on Jan. 7, 2015, murder happened not one by one, not in places far from the international seats of power, but to nine journalists killed at once, all shot to death, and four others wounded, on the second floor of a placid office building in the vibrant heart of one of the most fabled and civilized cities in the world—Paris.

These were murders directed not only at human beings, but at what those human beings practiced and stood for: the principle of free speech.

The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo long prided itself on being an equal opportunity offender, leveling its satirical barbs and cartoons at power, pomposity and hypocrisy wherever they were found, in places secular and religious.

Charlie Hebdo is no modern-day anomaly. It is the inheritor of a tradition of satire deeply embedded in French culture, in centuries of writers and performers. The magazines that were the immediate precursors of Charlie Hebdo were born, were banned, disappeared, sued, were firebombed and hacked, threatened, and at last reborn.

The staff of Charlie Hebdo is the recipient of the Los Angeles Press Club’s Daniel Pearl Award for Courage and Integrity in Journalism.

At Charlie Hebdo, threats were no anomaly, either. The magazine’s editor, Stephane Charbonnier, was among the dead, as was his police bodyguard. Charbonnier had told the French newspaper Le Monde several years before that his cartoons shocked “those who will want to be shocked… I don’t feel as though I’m killing someone with a pen… I’m not putting lives at risk. When activists need a pretext to justify their violence, they always find it.”

Extremists had firebombed the magazine’s Paris office in 2011, after the publication of an issue editors sardonically said had been “guest-edited” by the prophet Muhammad. Thereafter, the paper had moved to the location where the killers attacked this year.

After the January 2015 attack, the swell of support for Charlie Hebdo’s staff, and for the free speech rights it practices, was instantaneous. It was also international. The hashtag #jesuisCharlie leaped to the top of Twitter.

In September 2001, after the terrorist attacks on the United States, Le Monde had written forcefully that “we are all Americans.” Now, millions proclaimed, they too were French, they were Charlie.

With signs, with candles, with song, and with pens and pencils held aloft, the French massed in their cities and towns by the hundreds of thousands to show their support of free speech and defiance of those who would try to kill it. The message was also spread in cities across the globe.

Novelist Salman Rushdie, who knows what it’s like to wear a target, wrote in the Guardian newspaper after the attacks: “Stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity.”

Cartoonists the world over paid tribute to their professional kin with cartoons of their own proclaiming the pen’s enduring might over the sword: an automatic weapon arrayed against a mass of pencils; the Statue of Liberty, a French gift to the United States, cradling a copy of Charlie Hebdo in her arm; a masked terrorist cutting off the head of a pencil only to see a hundred more spring up in its place.

The week following the attacks, Charlie Hebdo was published on schedule, not with its usual 60,000 copies, but ultimately with a press run of as many as 5 million, the revenue going to the families of the victims.

Its cover: the headline “All is forgiven,” and a cartoon of the prophet Muhammad, holding a sign reading, “Je Suis Charlie.”

Charlie Hebdo journalist Antonio Fischetti, who had been attending a funeral when his colleagues were murdered, told the Liberation newspaper right after the attacks, “They wanted to completely eradicate a newspaper. This is not ‘just’ kill the editor. There are no words. This is really an act of war. All for drawings… Charlie had a mission, supported by some, opposed by others. I am even more aware today how important this fight is. We were all in agreement that we should not give in. But they decided to eradicate this symbol of freedom that was Charlie.”

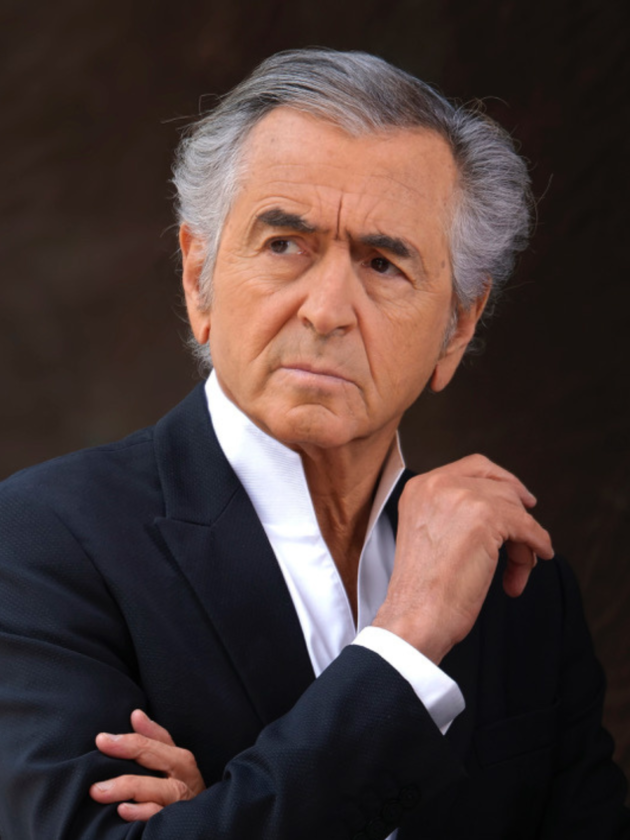

In fact, that still is “Charlie,” as the murders meant to intimidate have only served to steel the resolve and unity of journalists. Fischetti is here representing his colleagues, living and dead, to accept the Pearl Award.

The award was named for the Southern California journalist and Wall Street Journal reporter who was kidnapped and murdered in the line of duty in 2002, investigating Al Qaeda links to the shoe-bomber terrorist Richard Reid. Since that year, and beginning with Daniel Pearl himself, the award has been given to those who epitomize courage and integrity in journalism.

Those are traits clearly displayed in the work the staff of Charlie Hebdo did before Jan. 7, and the work the magazine continues to do today.